Note: spoilers for Dark Souls. Also aspects of this are taken from my writings elsewhere.

Located high in a tower overlooking a city slipping into a blackened abyss, a giant sits imprisoned and blinded by the very people he had come to save. The rest of the adventuring party he had arrived with are scattered, dead, or worse. But he is not afraid, having achieved a monk-like acceptance as the world progresses beyond his ability to do anything about it. So here he sits, cross-legged and hewing impressionistic wood carvings. At the sound of your footsteps he kindly greets you, a traveler from a distant time. He is one of the few in this land who does not automatically hold you in contempt or seek to manipulate your goals. With his greatbow by his side, long unused, this weary archer reflects on his life, “Exhilaration, pride, hatred, rage…The dragons teased out our dearest emotions. Thou will understand, one day. At thy twilight, old thoughts return, in great waves of nostalgia.”

It’s always weird to talk about something so taken for granted in some social circles only to find the need to explain from square one the topic for a completely different crowd. Where do you even start with for Dark Souls? A video game that arrived in 2011 during an impossibly stacked year that featured Portal 2, Skyrim, Uncharted 3, and Batman: Arkham City to name just a few. Initially known by reputation as “That hard game,” large swathes of players were turned away but thanks to fierce word of mouth they not only returned, but the game wound up winning a number of “Best Game of the Year” titles, nominated far more than that. It has gone on to spawn a subgenre in its name (“Souls-like”) and is frequently name checked on “Greatest Games of All Time” lists. It’s a game that birthed a whole cottage industry of passionate fans that has resulted in so much excellent work: from how three of my favorite people on the internet became best friends to Noah Caldwell-Gervais’s excellent five-hour deep dive on the trilogy and Chris Dahlen’s love letter to one of the game’s most frustrating levels (pair it with My Brother, My Brother And Me’s Justin McElroy’s parody hate letter to the level that comes next). There’s also VaatiVidya’s entire body of work which is followed by more than three million people. The game even wound up helping shape the aesthetics of Stranger Things1. All of this in and of itself has resulted in so much similar work that there has been an oversaturation, with some video game writing sites even going so far as to politely request no Dark Souls related pitches.

There is so much because Dark Souls *is* so much to so many. Can you say something new about Dark Souls within the crowded convention hall of all that has already been said? Can you even say everything that needs to be said, of lore and context and mechanical explanations, with the span of just one essay? No, and that’s fine. This is yet another Dark Souls essay, about the past, the present, for the uninitiated, the familiar. Over the past month I have played through the game for the first time in a decade. During that time I found an old friend, a Rosetta Stone translating my experience with so many different forms of art, and a frustrating great grandfather of a game, aged and rough. As I replayed the game, emotions and memories long buried came flooding back through new riverbeds formed by life. I found new ways to be frustrated, and unexpected kindness from strangers. In hindsight, I should have expected nothing less.

Appreciating Friction

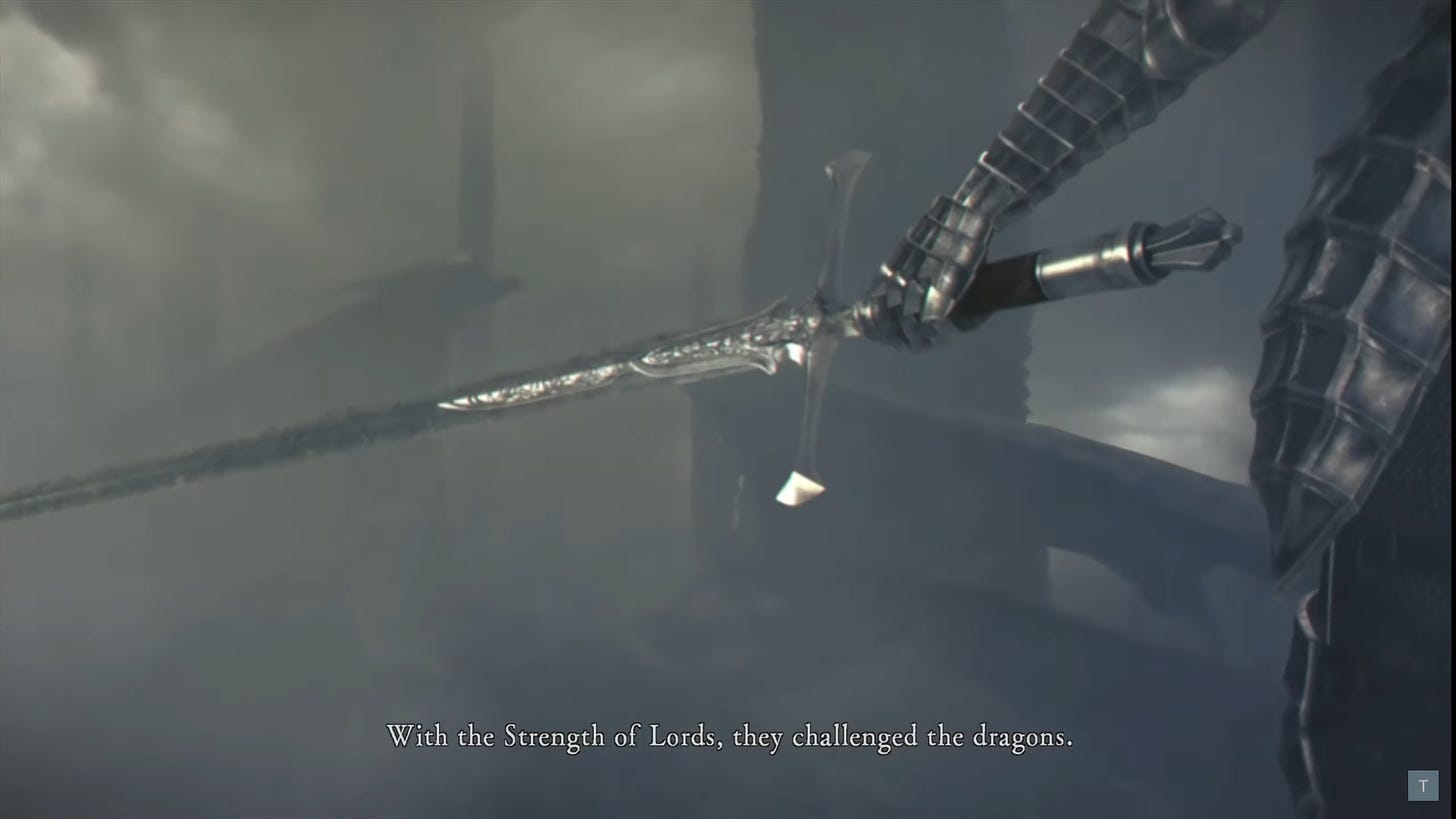

A rough pitch to describe Dark Souls for the unfamiliar could be “Lord of the Rings but all tragedy.” It is a fantasy world set long after the apex of its golden age and now what’s left is shadow and ruin. The game opens with a grand but vague cinematic trailer that summarizes the history of the world and the root of its strife. It ends and players are unceremoniously dropped into a jail cell. This is where its “hard” reputation kicks in as all that stands between you — the real start of the game is a rotund demon swinging a club that’s much, much larger than you, and you need to find a weapon. According to the PlayStation achievement statistics, 7% of players who started the Remastered version of the game (which came out seven years after the initial release2) never escaped this tutorial level. For players that do escape and make it to the main area of the game, it’s up to them on where to go next. There’s no map or compass, no instructions detailing quests that need completing or any of the number of obtuse systems like weapon enhancement or covenants that the player can join. Every character you meet that isn’t trying to immediately kill you usually ends their conversations in awkward laughter, most sounding as though they can’t wait to attack when your back is turned. This is where the design philosophy of the game reveals itself to the player, that a straight line path is not always the most interesting. In 2012, I had never played a game that gave the player this much freedom.

By 2011, the criticism that video games had become too linear had gained traction and not without merit. Video game design being made at the AAA level (of the highest budgets and team size) had begun to feel reduced down to having players move from point to point with scattered enemies in-between. In Dark Souls, level design frequently gives the feeling of working through a spiral, of moving up or down in the world and unlocking shortcuts between the layers. At one point early on in the game, after making my up way through a medieval town filled with zombies and above it into a castle church guarded by heavily armored knights, I hesitantly stepped, battered and bloodied, onto an elevator platform. Instead of taking me up like I expected, it took me down — all the way to the game’s first real safe space, a location that I hadn’t seen in hours. Now I could move between it and the church with ease. I remember the feeling of being floored at that reveal, as though I needed to look around and ask aloud, “Can video games do this?” Having all areas containing at least one shortcut leading to a bonfire where you can rest and regain your health is what elevates Dark Souls beyond simple masochism, which would be the case if it had incorporated a more linear design while keeping the enemies as vicious as they are.

Within this obfuscated level design are of course many, many terrible things, of knights, dragons, and all manner of weird creatures between you and your goal (you are never prepared for your first mimic). But they often serve a larger purpose than simply beating up players and stealing their hard earned currency. Dark Souls introduced to me the concept of “environmental storytelling,” of the game not going out of its way to tell you specifically what happened in the spaces that you will travel through. That was all up to me, to put together contextual clues from enemy and item placement as well as crumbs of lore from item descriptions. In the grand scheme of the game, an escaped crystal butterfly that has flown down from the highest level or a taurus demon that has made its way up out of hell show the scope of the game’s emphasis on verticality. Coming to appreciate this design philosophy, of discovery being given greater value through personal engagement, has impacted how I view everything from other video games to film and literature. It unlocked the concept of meeting the work of the artist on their level instead of based on personal expectations which was greatly needed for fresh-out-of-undergrad me. Beating Dark Souls came with a desire for a greater understanding of art, of both first-time experiences and reappraisals. That which I had initially dismissed as being too difficult often turned out to have so much meaning than I had often dismissed off-hand. This concept of not settling just because something is hard also began to bleed into the rest of my life.

Any preliminary search among Dark Souls fan videos or writing and it won’t take long to find stories of people at their lowest finding a form of stability within the game, of steady forward progress coming to mirror real life hope. I am no different. I’ve written previously about the worst year of my life3. In the background of that struggle, I slowly made my way through Dark Souls for the first time and the parallels wound up closer than I could have ever guessed. In the real world I had become stuck, isolated in a dead end job, and in the game I was trapped in a dead city.

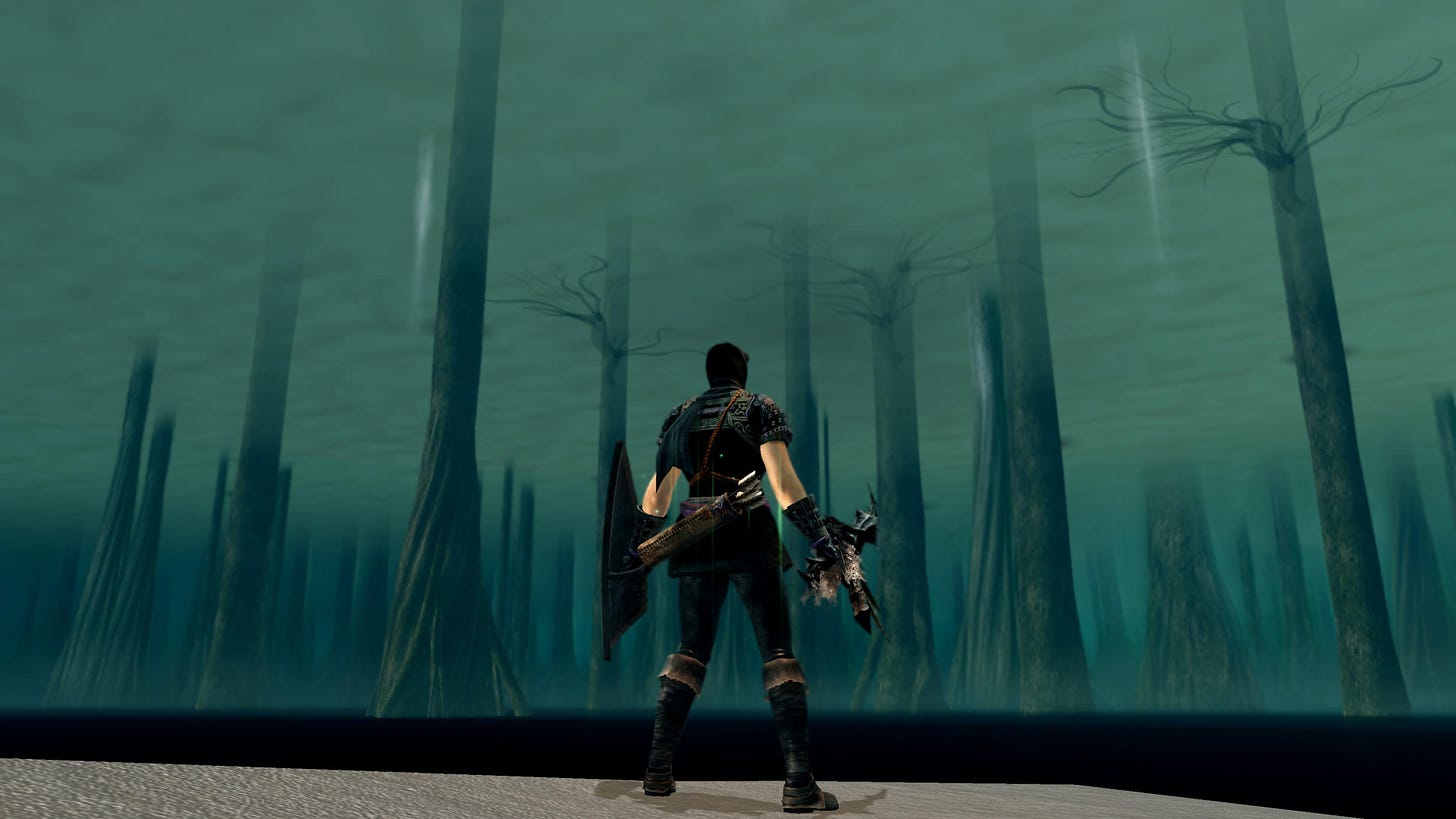

Dark Souls is a game of two halves. In the first, the player’s goal is to ring two bells in order to unlock access to the city of the gods. In the second half, your task is to eliminate four bosses whose power you can collect in order to fundamentally change the world. There’s Seath, a pale crystalline dragon, the Witch of Izilith who has become a fire-breathing tree, and even the Grim Reaper, Gravelord Nito4. Then there are the Four Kings, the Dark Souls answer to Tolkien’s Ringwraiths. They reside in a flooded city just below Firelink Shrine, the game’s starting area, and since there is no instructions about where to go, new players are prone to stumbling down to their doom in the ghost-infested outskirts. Fighting the Kings is stressful for a number of reasons. It takes places in a blackened abyss that requires the use of a ring in order to even reach, taking up one of two precious ring slots that give your character various stat boosts. Being an abyss, it is devoid of landmarks to help you get sense of the space between you and the Kings who continue to spawn at fixed intervals so it’s easy to get overwhelmed in multiple ways. As with any any area of the game, you can summon other players to help you take on a boss but doing so gives the boss extra health. With the Four Kings, this means that bringing in another player will likely help the Kings if you and your companion’s damage output is not high enough. More than for any other boss, the odds feel overwhelmingly stacked in favor of the Four Kings.

The thing about the games made by FromSoftware, the studio behind Dark Souls and its family, is that everyone’s experience is different. One person’s brick wall is hardly even a speedbump for someone else. But to approach all of the game’s problems through brute force alone would create a slog. With just a handful of poison arrows and a measure of patience, a player can save themselves a significant amount of grief throughout. Moments where I can out think a situation, investing minimal effort for maximum reward, come with the same rush as finding the right puzzle piece. But there are moments where no matter the person’s playstyle, the scope narrows down to just you and a boss you can’t get the hang of. I do not begrudge FromSoftware having difficulty spikes because having every challenge be the same would result in a flavorless experience that plateaus early on. But the initial meeting between wall and player can feel debilitating. For me, the Four Kings were all that was left before the game’s last boss. I distinctly remember the thought that I could just give up, that it was just a game. But I didn’t and over time, I incrementally got better, through further leveling up my character and by simply learning when to dodge their attacks. But for as much as they made me suffer, I can still recall the feeling of despair at being stuck, I do not remember that specific victory. It’s likely that what came immediately after their defeat eclipsed any prior triumph.

The moment I remember clearest is finally beating the game. The last enemy to fell is Lord Gwyn, the god who ushered in civilization at the dawn of time. He is a charred husk of his former radiant self, having given his body over to a primordial fire that supports all life, lest it go out. The musical theme is far from bombastic, a simple melancholy piano motif that ebbs and flows to the duel between your character and a withered god who has outlived his usefulness to the world he shaped. I sat on a worn couch in what at the time felt like the bottom of the world and I beat Gwyn on a sweltering summer day. There was no shouting of celebration but a simple assured feeling of completion that I can still feel traces of. With Gwyn gone, there are two endings to the game, both intentionally vague. Do you relight the fire, to let new life flow once more knowing that you will become like Gwyn and it will eventually begin to burn out again? Or do you walk away and give a new world a chance? There are clues throughout the game that neither choice is completely good or bad. For whatever reason, I walked away from the flame, choosing a more unknown future. Looking back now the parallel is almost cliche. A short time afterwards, I quit the job that kept me trapped, taking a leap at living in Denver, far from any friends or family. It turned out to be one of the best times of my life.

I would not beat Dark Souls again for eleven years.

What Comes After Fire?

It’s hard not to hold what came next to the standards of “first time experience.” The two direct Dark Souls sequels were both critical and commercial successes but neither personally lived up to the first game. The second tried a lot of new things to complicated results but because it immediately followed in the footsteps of its predecessor it has something of a complicated legacy though far from without very vocal defenders. Dark Souls III arrived just two years later and as perhaps an over-correction response to Dark Souls II, bringing back a host of familiar locations and enemies which makes for a somewhat lacking experience to play but fascinating metatextual analysis about how a world forced to repeat itself is a hollow world. Over this span of time, the series began to be eclipsed by its own in-house siblings, with Bloodborne (2015) and Sekiro (2019) reaching new heights of art design and rewarding challenge5. In fact, Sekiro would become something of an emotional load bearing piece of art for me at the height of COVID. Easily a 40 hour game, I got to the point where I could beat it in under 8, its rhythm-based combat becoming like a favorite album as the world outside burned with fever and political turmoil. Then Elden Ring arrived in 2022 and eclipsed, well, everything. Just two years after its release, it’s already one of the best selling video games of all time and still climbing. It nearly swept all major video game outlet awards. The game itself is so large that you are given a horse to help speed up traversal. There are such demanding boss fights that I’m half-surprised I’m still not stuck with them. It is all both an expansion and refinement to the nth degree of everything that Demon’s Souls (2009) first hypothesized and that Dark Souls popularized. But even as I have played through this great feast of a game many times over, I couldn’t help but think about what came before.

The natural flow of Dark Souls sends players spelunking to the depths of the world, of darkened crypts and lava-flooded ruins. But there exists a deeper level. Down from Firelink Shrine, down from the Four Kings’ flooded city, is Blighttown, a wretched shanty town and poison swamp that hides the second bell and is the breaking point for many players6. At one end of the toxic mud pit is the bell and at the other an enormous dead tree. At its base, a root leads up to a nook and inside a body clutches a hastily constructed shield. There’s nothing special looking about that small hole in the tree unless you for some reason roll into or take a swing at the back wall. Doing so will reveal that it’s an illusion, another small room behind it with a treasure chest. Hit the back wall again and it’s another illusion, this time opening up into the interior of the tree. Follow the treacherous root path down, far, far down, and you’ll emerge into a level has fallen out of time. Set to a truly looming piece of choir music, Ash Lake is a primordial pocket of the world as it once was before Lord Gwyn culled the dragons; you can even find possibly the last scaled survivor of that war. You are unable to deal damage to this beast, no matter how hard you hit, indicating just how great its kind once was. You can also use contextual clues to realize that the sand you’re walking upon is actual ground up dragon scales. The odds are high that without guidance, the average player would never find this level on their own, the swamp alone dissuading a large percentage from even approaching the tree. Much of modern game design is centered around checklists, ensuring players not miss a single thing, and in doing so become a slog. Dark Souls comes with multiple hidden levels like Ash Lake. Sometimes I can’t help but hold all that has come since to that same sensation of discovery. I also recognize that the game chides such a desire.

The nature of Dark Souls, both in-game and metatextually, is cyclical. You beat the game and it puts you right back into your starting jail cell. The fire is always dying and someone always willing to restart it. Enough time has passed and attention given since release that really most things that can be said about the game have been and will be said again. It all breeds familiarity, though this qualifier does not automatically means “bad.” The term can mean a great deal of comfort as Dark Souls has come to be for so many. But the series speaks on this, that forsaking the future in order to hold onto the past breeds stagnation. This was after all the thesis of the final game, Dark Souls III, showing players a world devastated by this arrested development ideology. Eight years since the release of the final game, the world has come to further mirror this with so many of the forces that drive art of any medium right now being reluctant to let go of the past, seeking to continuously mine it for value. FromSoftware’s refusal to release sequels for the sake of having a release is increasingly at odds with the ethos of the wider pop culture landscape7.

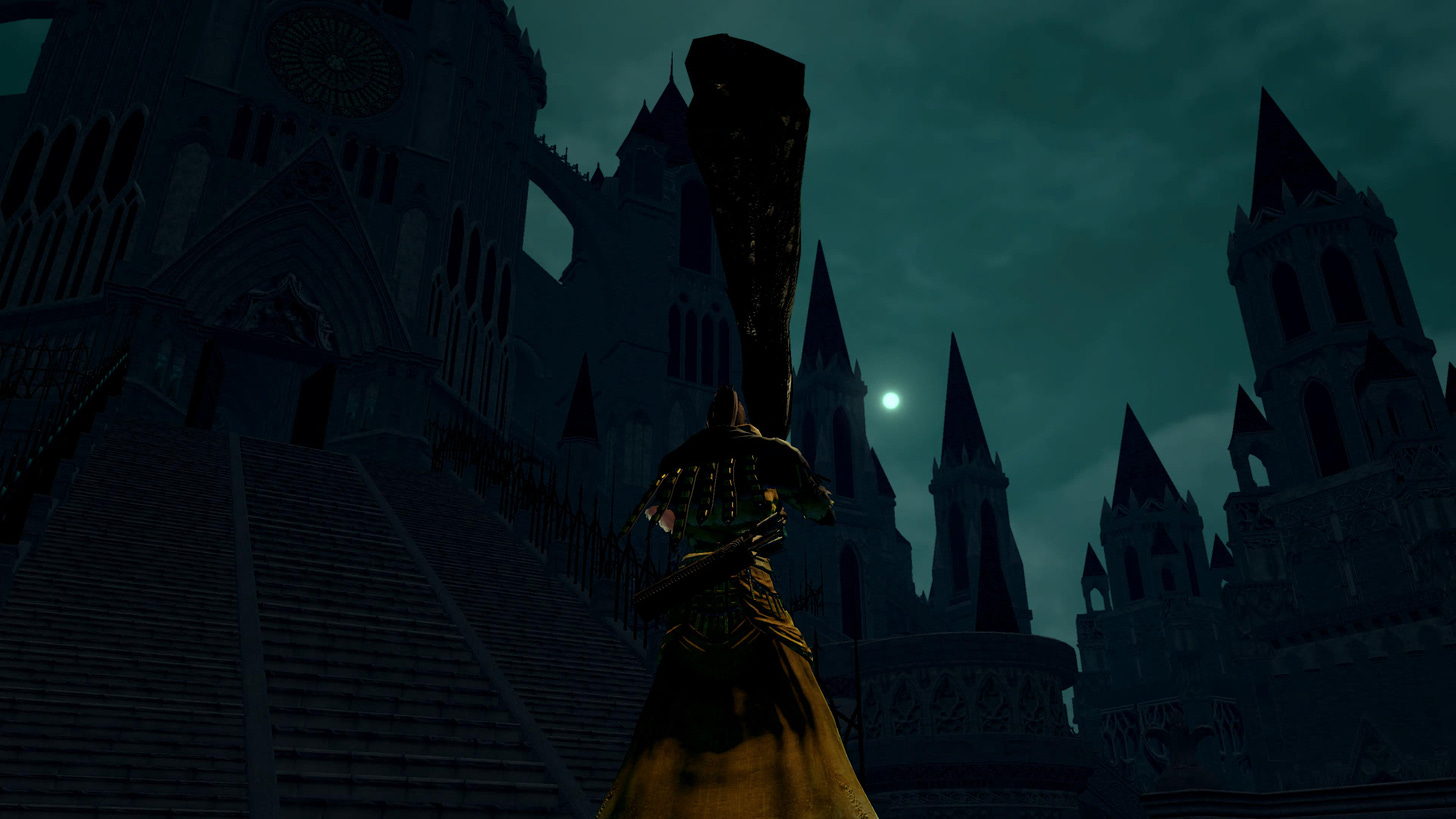

Halfway through Dark Souls you reach Anor Londo, city of the gods, brilliant and bathed in radiant sunlight. But it hides a dark truth. You can uncover this by shattering the illusion created by the last remaining god, a minor one who is in hiding but still capable of great power. When it goes, so does the sunlight, revealing that the city has long since fallen into twilight and largely abandoned. There are hints of this truth throughout the level, of askew portraits and peeling wallpaper, but the full reveal weighs like little else in the game. Taking this course of action results in many enemies disappearing, leaving you to wander the cavernous halls in mausoleum moonlight, the only sounds heard anymore are the player’s footsteps and the steady hammering of a lone blacksmith. What Anor Londo becomes is uncomfortable but it is the truth, acknowledging that the world has moved on. Change is a force that not even Gwyn could halt as the most powerful of gods, and his refusal to adapt harmed the world.

I very much wrestle with the question of “Is a piece of art good or was it your first experience of that kind?” I am not immune to becoming stuck on a work of art that has come to carry significant meaning. This is not to say I don’t seek out or enjoy new experiences. There has been plenty of music, movies, and games since Dark Souls that have further evolved the landscape of my tastes. FromSoftware has also refined itself at both micro and macro levels of game design, continuing to encourage players to engage with their art in a time where playing video games often feels like being seated in a restaurant and having food slopped on the plate. Just over the past year alone, I had my breath taken away by an array of FromSoftware experiences, from a secret abandoned village bathed in rays of gold that recontextualizes much in Elden Ring to battling a giant mechanical ice worm in Armored Core 68. But behind it all, Dark Souls lingers, its experiences returning to me like the déjà vu of new friends who look like ones I used to know.

Old Comfort Clothes, All Their Holes

When I need to farm9 or want to simply zone out while playing certain video games, I will mute the TV and Bluetooth music through the speakers. I also do this when dealing with particularly tough bosses. As David Byrne sang about recognizing that this must be the place, the dreaded black dragon Kalameet, whose wrath the champions of Anor Londo dared not risk, finally went down. There had been over a decade of life since the last time I had faced him.

On a whim, late into the 2024 summer, I decided to return to Dark Souls. I had spent most of the months prior playing the new expansion for its great-grandchild, Elden Ring, and the heights that it demands players scale in order overcome its challenges are dizzying. In the wake of completion, I wondered what it would be like to return to a slower paced game, to trace the roots back to the trunk. I had made a few half hearted attempts in the years prior to play through the Remaster but never made it further than reaching Anor Londo. With video game consoles advancing several generations since my first time playing Dark Souls, I was able to record my experience in all of its nostalgia, aging graphics be damned. The results as you can see below are humbling.

This struggle to kill a low level enemy is a good 30 second summary of the “learning Dark Souls” experience (or in my case, relearning). Weapons bounce off walls, swings miss the enemy, enemy attacks halt your own, button mashing ensues so that instead of attacking you accidentally kick the enemy. It made me feel fat fingered and angry, just as the game had done so many years ago when I first played it. But this time it also came with the knowledge that I had beaten it all before and could do so again. It had taken me around 100 hours to finish my first playthrough in 2013, of fighting my way through the highs and lows of the game. It all felt enormous, of the level design that spiraled out from me in any direction and all the challenges that paved the way. I beat Dark Souls twice this summer in well under that time.

Having grown and absorbed so much commentary about the game since the last full playthrough, returning felt very much like a rereading a book that’s become well worn out of love, but one that happens to make you fight for every page. So many sensation were stirred up anew, of working my through levels and overcoming their obstacles. Ash Lake still brought about awe, the tragedy of the world did so for grief. On the flip side, the rougher parts of the game feel even rougher now, such as the fact that the Lost Izalith area is just three reused early game bosses stacked in a trench coat of an unfinished level before you get to the most annoying boss fight of Dark Souls. But there was an element of the game that was completely brand new to me, one that I had only grown to know in other subsequent FromSoftware games. Now with 2013 long grown small in the rearview mirror, I realized that Dark Souls is a very funny game.

There’s a story I think about all the time when playing FromSoftware games. Variations abound but it boils down to an astronaut circling the earth in a spaceship. One day a panel starts to beep and does not stop. Mission control is no help, unsure what is causing it from their remote end but they’re sure it’s not life threating. No matter what the astronaut does, resetting the machine, taking it apart and putting it back together, nothing stops the noise. There’s two choices: either let the beeping stay a nuisance or come to accept it. So it becomes part of the natural soundscape. Dark Souls wants to elicit multiple emotions from you, not just rage at defeat. There’s plenty of that as well as sorrow gleamed from the tragedy of this world but the thing is, this is also a game that wants to make you laugh. How can you not when you walk into a room and see that the only way forward is a narrow walkway populated with comically large swinging axes? Accepting the difficulty of Dark Souls as part of the landscape instead of *the* landscape itself allows for the player to recognize the distinctions therein. Dying may be a setback, a costly one at that, but learning to laugh at it makes the game all the richer.

Across the gulf of time between full playthroughs, I came to a greater appreciation for classic black-and-white/silent films, specifically those of Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin. The comedy of their films is timeless, both little guys who the world is constantly dunking on. They also often contain some of the most breathtaking stunts that beg the Mad Max: Fury Road question of “How are people not dead after filming such a scene?” Houses fall on them, machines devour them, and still the characters bounce right back. Their pratfalls feel like any number of fates that can send your character to their doom. Floors fall out suddenly, Indiana Jones-style boulders appear out of nowhere, the aforementioned swinging axes. That there is a split opinion on the worst enemy to deal with, either Spirit Halloween skeletons stuck in a wheel or long-running googly eyed lizards10, says a lot about the design goals of FromSoftware: who says you can’t laugh while running in terror?

As I continued to replay the game, with the pressure of needing to beat it removed by familiarity and new understanding, I understood that it would likely be a long time before I return, if ever. Replaying it already felt like visiting with an friend who it’s fun to reminisce with but that only goes so far. So I decided to pursue all the achievements the game has to offer. Meeting these ranged from simply defeating certain bosses to more obtuse goals, like upgrading a weapon to its fullest for every damage type. The most difficult achievements are of the checklist variety: collect certain spells, miracles, pyromancies, and rare weapons. Since these final achievements only unlock when gathered on one character and many of these items are locked away due to what choices you make, multiple playthroughs are required to gather them all. The catch though is that the game gets more difficult each time you beat it. Enemies get more health and hit harder all the while the levels you are gaining eventually plateau in their effectiveness. This didn’t phase me, especially at New Game+11 when I was vastly overpowered due to how far I leveled in the previous cycle. It was in the next cycle that everything went wrong.

By the time I reached NG+2, I had just two achievements left to unlock: to find a secret covenant and to forge one last sword, one that could only be done by defeating a certain boss so I would only have one opportunity to make it that whole cycle. The boss went down easily enough but while looking at the wrong line in a menu, I promptly created a sword I already had. The feeling of defeat was compounded by the ordeal of the other challenge left. At that point, I was ready to be done with my time in Dark Souls, the fun of catching up with an old friend was reaching a point where all that could be said was running thin. In NG+2, the enemies had surpassed me once again, the strongest of armor doing little to stop low level enemies from taking chunks out of my health if I wasn’t careful. As fate would have it, in order to find the last covenant, all I had to do was defeat my old arch enemy, the Four Kings, now doubled in strength. I wouldn’t even be able to forge the correct sword on the next cycle without going through them but I was stuck once again, overwhelmed and frustrated. So with the energy of Homer Simpson desperate to escape New York, I stacked level upon level of health, wore the heaviest armor possible, swung the biggest weapon I could find, and ground my way back out of the abyss.

All that was left was the matter of the sword. Correcting my mistake would mean pressing on through the second half of NG+2 and through the first half of NG+3. I felt exhausted by the prospect and defeated by how close I had come. Then like a cliche from some legend of old, at my lowest I found what I was looking for: I remembered FromSoftware’s thesis that you are only alone in suffering if you chose to be. To that point, I had not engaged in the game’s multiplayer system, of dueling or assisting (or be assisted by) other players. I had researched that another player could simply give me the missing sword and the achievement would unlock. So out of desperation, I turned to a community of FromSoftware fans and posted in a Discord group asking for help. An hour or so went by and no response, and I came close to deleting the message, socially very anxious about being vulnerable in regards to a mistake that I had made since the modern internet is frequently a mean spirited space. Then I got a response from another player, expressing their excitement at the opportunity to help a fellow Boston Red Sox fan12. After much trial and error, I was able to summon them into my game and on the hallowed sunlit streets of Anor Londo, I was handed the sword and the final achievement completed. In the video below you can see me emotionally glitching out before dancing with joy.

Even at the very end of what could be the last time I play Dark Souls, even as I had grown sick of it through cyclical frustration and familiarity, the game continued to surprise me. Great art teases out an array of emotions, not just frustration. It invites cooperation through different perspectives and insights. Dark Souls achieves all of that13 but is also one of the rare instances where both the text and subtext of the artifact push the audience onward. It is still a deeply rewarding game for everyone who has the willingness to adapt to new experiences. It’s also okay to return and rest at a bonfire for a time but the world itself, of art and time, will keep progressing no matter what. Sometimes you need help keeping up and that’s fine. It’s the effort to keep trying that matters.

Those claims feel like a bit of a stretch but still, to be name checked by the forces behind such a pop cultural force.

The 2018 Remastered version really only offers a slightly better coat of paint over the original game.

Knock on wood that that was as bad as it ever gets.

This is to say nothing of the “Souls-like” sub-genre that surged out from 2011 with games like Hollow Knight (2017) and Lies of P (2023). Youtuber Iron Pineapple has a long running series that showcases the scale of this influence.

That the game released with technical issues that would occur in the level absolutely added to this frustration.

This topic is more complicated than is afforded here but even as rushed as some productions were, such as Dark Souls II being announced just a year after the first, but even with my personal feelings towards the game, there’s no denying that great effort went into its creation to not just settle for being “Another Dark Souls.”

Though significant spoilers, these experiences are worth sharing, especially for those who might not otherwise see them. Personally feel that the Ice Worm fight might just be one of the most exciting boss battles I’ve ever played.

This is when players intentionally repeat an aspect of a game in order to acquire experience/levels, resources, or equipment.

I’m well aware that what most people assume are the eyes actually aren’t.

To explain the New Game classification system: NG is your first playthrough, NG+ is your second, NG+2 and upward are all subsequent times.

There are few things I hate more than coming up with a new user name so variations of Red Sox have been used for decades.

I do greatly miss the days where the mysteries of FromSoftware games were slowly pieced together across message boards.